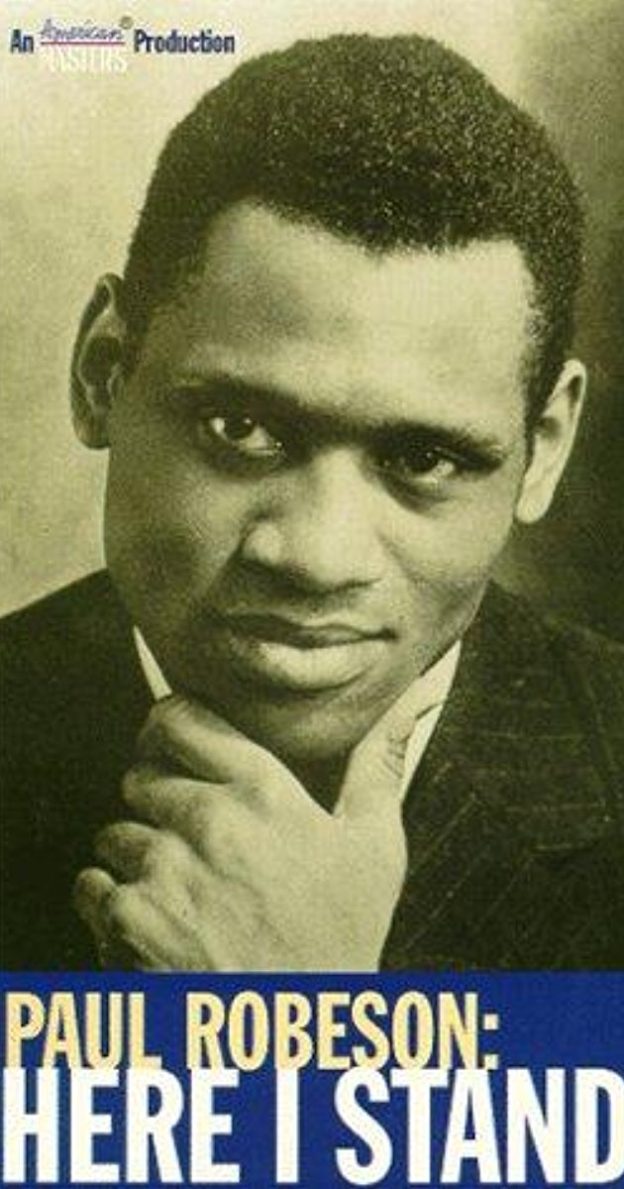

I’m so glad we watched “Here I Stand,” the documentary film based on Robeson’s autobiography of the same title. Having read the the book, the film brought to life so many of Robeson’s words–words I understand as important declarations concerning freedom, black humanity, and the role of the artist in shaping the world.

Reading the autobiography had not prepared me for the impact of seeing and hearing Robeson himself describe the time when the Rutgers football team–a group of his peers–held him down and removed his fingernails. Reading about it was chilling enough; think for a moment what it would mean for a person, a human being, to survive that kind of torture and then thrive–and return to the historical record even after so many attempts to erase him.

And, in terms of our conversation last week about privacy, and questioning the very notion that black individuals could neither claim nor enjoy it, I am even more struck by Robeson’s experience: His father sent him back to Rutgers even after white students assaulted him–breaking his shoulder and his ribs, on one occasion; removing his fingernails on another–because his father knew that if he quit, the black students that followed would have even less of an opportunity. This requirement that young people volunteer for torture (think about those kids integrating schools, or the college students sitting at lunch counters, being taunted and spit upon, for instance) is the price young people pay for the possibility of freedom. Robeson was a teenager. He had to swallow his fears, his expectation of safety, and his own blood in order to claim his rights as a man, as an American. His example is one more reminder of the ways in which black people–as individuals and as communities–had to give up so much of themselves (in bodily and psychic safety) in the service of justice. When does the sanctity of the person as human mean in this context? This is the point Hannah Arendt was getting at when she wrote her essay “Reflections on Little Rock.” For her, there is no love in politics. James Baldwin’s indirect reply pretty much sums up the paradox: black freedom struggles require that level of sacrifice, a sacrifice out in the open, in public, because the private experience, the nightmare really, is just as bad.

And then, there is there is the question whether justice can be won at all. If the presumption is that black people and people in the struggle for recognition, and for legal equality, always have to be willing to publically expose themselves to pain and hardship in order to claim the rights they deserves as Americans, even as persons, is that a victory? What’s more: the requirement that Robeson had to perform better than every other white person, persons who had the freedom to expect safety even while terrorizing another human being, is astounding. Does recognizing black humanity require black super-achievement?

My point is really about the contradictory praxis of concepts like freedom, equality, and justice. Robeson’s declaration, “[t]he artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative,” makes this point especially clear. Indeed, he had no choice. Any artist who thinks they can work outside of politics is also making a choice, one that assumes the logic of freedom and equality that does not include marginalized people.