Mad “ Of a person, action, disposition, etc.: uncontrolled by reason or judgement; foolish, unwise… of a person: insane, crazy; mentally unbalanced or deranged; subject to delusions or hallucinations” (OED)

Apply the definition above to females, and you have the recipe for the madwoman. Across much of 19th-century literature, these women scour pages scaring heroines into the waiting arms of their heroes. The madwoman is typically marked as a villain, nothing more than a monster to scare readers. However, looking deeper into such works, the madwoman is a victim of the same patriarchal society that the heroines and their authors are a part of. Historically these women exist as well, their fates often much less poetic than their literary counterparts. While it is easy to write these women off, to believe that their madness is something wrong with them. Madness is subjective, a historically constructed category that gets differentially applied to individuals depending on their status: gender, race, and class. This construction continues to this day, and in this contemporary moment, status is now influencing COVID-19. As many are experiencing their own isolation and quarantine, societal disparities are ever more apparent. To focus on gender disparities, the virus is a backdrop to the discrimination women have faced for centuries. The virus has exacerbated issues such as domestic abuse, the wage gap, harassment, and ultimately the patriarchal domination that suppresses them. The madwoman has not disappeared in novels or in real life, she is still clawing beneath the wallpaper. To understand madness in our contemporary moment, it is useful to revisit the depictions of madwomen in 19th-century literature, as such ideas about madness and gender continue to impact us today.

An important distinction that needs to be noted is that these women were often not clinically mad at all, but rather non-conforming. Historically (and arguably still now) patriarchal society could not recognize women aside from the submissive female. If a woman was to put a toe out of that box; meaning that they had opinions, spoke on those opinions, wanted some freedom, and maybe even liked sex, they could be condemned as mad. An example of this (that will be further addressed later) can be seen in Bertha Mason from Jane Eyre. Very little is revealed in Brontë’s novel about Bertha’s past and her thoughts–all readers know about her comes from Rochester. Rochester claims that her madness is a result of her genetics, however, a more apt reason could be that she did not fit into the English wife he wanted her to be. When he could not ‘tame’ her he gave up, locked her away, and moved on to his next target: Jane. The true core of this issue comes from the way society is and continues to be structured. Those who society values (white men) are placed at the top, giving them the resources and power to distribute to the rest below them. The top becomes the norm that everyone else should strive to emulate. The restrictive nature is what both creates and condemns the madwoman.

The reason there are madwomen and not madmen is clear: at no time has there been anyone governing a man in the same way they have, and continue to govern women. Women have always been, “enclosed in the architecture of an overwhelmingly male-dominated society” (Gilbert & Gubar xvii). Women go mad when the pressure to conform becomes too much. In a twisted sort of way, madness is the most freedom a woman can have. When a woman goes mad she loses all semblance of polite behavior and societal niceties, and therefore, unable to remain a part of genteel society. The end result of madness is the removal from society. Removal here referring to being locked away; swept under the rug; out of sight, out of mind. Society does not have room for those who cannot conform.

Fast-forward to the 21st-century and female madness is running rampant once more. Within the last year, the world has faced an unprecedented virus (COVID-19) and the resulting lockdown. To add to the madness, the pandemic is only a mere prop to the corruption, protesting, and larger social unrest. In many ways, this pandemic has emphasized the already existing disparities in our society. For all, but especially women, COVID-19 has escalated issues such as domestic abuse and mental health issues. The New York Times has released figures that show one-third of jobs currently held by women have been designated as essential. This puts women on the frontlines and therefore at an increased risk to contract the virus. This is especially true for women of color, whom’s jobs are more often deemed essential than white women (and primarily white men). These positions have also, “often been underpaid and undervalued—an unseen labor force that keeps the country running and takes care of those most in need” (Robertson & Gebeloff). Our women continue to be seen as expendable: only necessary when there is no other option. All together this pandemic has simultaneously put them more at risk by making their jobs essential but has also pushed women back into their homes which also have the potential to be harmful. Neither the private nor the public sphere are safe.

Staying in one place for too long without much social interaction has been shown to cause psychological damage to a person. Right now leaving the house also has the potential to cause physical damage (i.e. contracting COVID-19). Remaining in the same four-walls during this pandemic has a parallel to 19th-century female writers and characters. As Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar note many female characters and writers of the 19th-century involved: “images of enclosure and escape” (Gilbert & Gubar xvii). These images are usually represented via “fantasies in which maddened doubles functioned as asocial surrogates for docile selves, metaphors of physical discomfort manifested in frozen landscapes and fiery interiors-such patterns recurred throughout this tradition” (Gilbert & Gubar xvii). Meaning that being enclosed both in their own homes, but in the patriarchy as well, led to escape-fantasies in which their true selves, or their mad-selves, could escape and be free. At this moment 21st-century women are experiencing our own kind of enclosure. Our own isolation has created a likeness to the madwoman character. We are stuck in one place, but our minds are running wild. Escape fantasies can be reality if we take this contemporary moment and make our voices heard. We can make the changes that have been a long time coming. The truth of the madwoman is that she cannot live caged in the patriarchal society forever. 19th-century female writers knew that, but there were few ways to escape on their own so they created their madwomen as a way to live the freedom they themselves could never fully achieve.

Madwomen move freely through 19th-century works, while their docile heroines remain locked away. In the case of “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, the heroine becomes the madwoman meaning that there are not two distinct female characters as is usually common in literature of this kind. Instead, readers see the full transformation from a submissive wife to madwoman which does read like two distinct characters, they just happen to be in one body. In this short story, a wife is advised, more like ordered, by her husband to remain locked up in an “atrocious nursery” (Perkins Gilman “The Yellow Wallpaper”). She has just had a baby and is not faring well. Right off the bat, Perkins Gilman shows the struggle her heroine is in. She knows there is something wrong with her, but the patriarchal figures around her do not believe that there is anything medically wrong with her. Instead, they decided to just sweep her off, away from prying eyes, away from the society she cannot conform into. She states, “if a physician of high standing, and one’s own husband, assures friends and relatives that there is really nothing the matter with one but temporary nervous depression—a slight hysterical tendency—what is one to do?” (Perkins Gilman “The Yellow Wallpaper”). What the heroine is actually suffering from is postpartum depression, which was not a recognized disorder at the time. She is quarantined upstairs where she becomes obsessed with the wallpaper and increasingly worse off. She becomes paranoid, distrusting her husband’s intentions, “he asked me all sorts of questions, too, and pretended to be very loving and kind. As if I couldn’t see through him!” (Perkins Gilman “The Yellow Wallpaper”). The patriarchal hold over eventually breaks when she snaps, becoming utterly mad, peeling all the wallpaper off and pacing around the room continuously “‘I’ve got out at last,’ … ‘and I’ve pulled off most of the paper, so you can’t put me back!’” (Perkins Gilman “The Yellow Wallpaper”). There is no going back into the wallpaper, there is no going back to the submissive wife.

Throughout the entire short story the narrator feels in herself, that if only she could write, her condition would improve. Her husband prevents her from doing so, instead recommending that she rest. Her voice is being taken away from her both in the oral and print forms. This sort of erasure is common across past and contemporary moments. With her transformation she surpasses the patriarchy, “now why should that man have fainted? But he did, and right across my path by the wall, so that I had to creep over him every time” (Perkins Gilman “The Yellow Wallpaper”). She physically and metaphorically tramples over the patriarchal hold over her. In this contemporary moment, we are seeing the results of centuries of oppression, like this, beginning to crumble. Many are expressing a desire to return to normalcy, but what normal are they referring to? The normal where women can be easily silenced by locking them away? Where minorities are actively discriminated against and harrased? We have a new wallpaper to peel down “in the midst of this terrible despair, it [COVID-19] offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves” (Roy “The pandemic is a portal”).

Like the narrator in Perkins Gilman’s story the original madwoman in the attic: Bertha, from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, is too trapped in isolation by the patriarchal structures in her life. Bertha never gets to speak to readers and is portrayed as the villain, the final obstacle standing between Jane and Mr. Rochester. Bertha as a villain makes sense on the surface, but looking deeper she is the ‘failed’ wife of Rochester. Yet again, the patriarch is the one to deem the woman ‘mad’. Rochester claims that “she [Bertha] came of a mad family; idiots and maniacs through three generations! Her mother, the Creole, was both a madwoman and a drunkard!” (Brontë Jane Eyre). To note on the Creole background of Bertha, Rochester is claiming madness in a family of a mixed racial background. Creoles were already at a disadvantage due to the color of their skin and could also be the result of rape and/or a coercive relationship. Perhaps the drinking is a way to escape the knowledge that they are meant for better things, but are being prevented from achieving them. Perhaps these three generations are all women who attempted to fight back against the society oppressing them only to be crushed back down. The fire Bertha sets later in the novel, is the same fire Rochester tried to put out in her.

If Bertha is the villain then that makes Jane the heroine, but as Gilbert and Gubar note, it may not be that simple. Jane has never quite fit into the mold of a ‘lady’ either, and “despite Miss Temple’s training, the ‘bad animal’ who was first locked up in the red-room is, we sense, still lurking somewhere” (Gilbert & Gubar 349). Bertha failed to fit into the submissive wife role that Rochester, and the larger society, required. Who is to say that after Jane and Rochester have been married for a time, that she won’t go ‘mad’ too?

Although these madwomen were not quarantined because of a virus, the intense oppression they experience is not unique to their stories. Today women are facing different versions of many problems that have plagued them since the dawn of the patriarchy. The madwomen show us how toiling under the patriarchy is suffocation. Female writers dreamed of freedom, but their resistance was often subverted. Many of their works play out the madwoman character, showing the “common, female impulse to struggle free from social and literary confinement through strategic redefinitions of self, art, and society” (Gilbert & Gubar xviii). Perhaps COVID-19 provides women with an opportunity to claim the madwoman and make our voices heard. Roy writes, “we can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred…or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it” (Roy “The pandemic as a portal”). We can continue to lock our women away when they try to rise up, or we can fight for our madwomen.

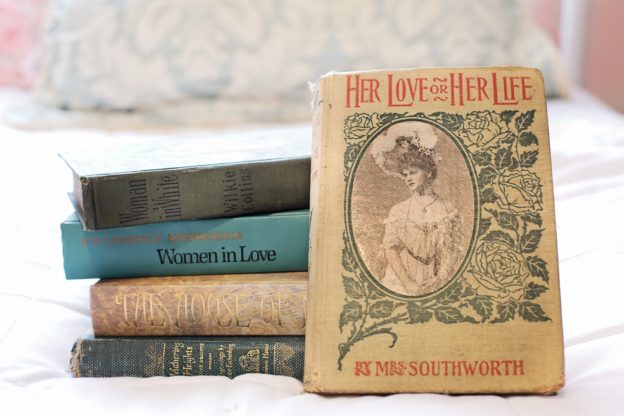

(Title Image courtesy of Jill Wellington from Pixabay.)