In the introduction of Zora Neale Hurston’s Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” she writes:

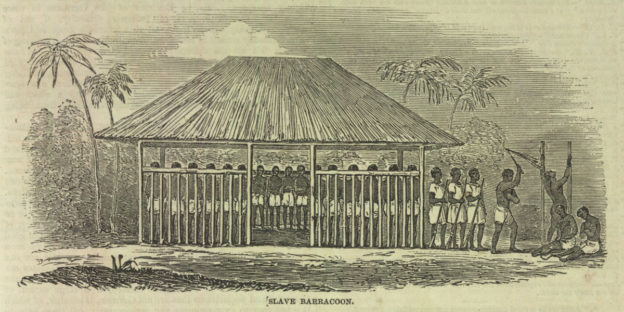

After three days, they were incarcerated in the barracoons at Ouidah (Oh-we-dah), near the Bight of Benin. During the weeks of his existence in the barracoons, Kossola was bewildered and anxious about his fate. Before him was a thunderous and crashing ocean that he had never seen before. Behind him was everything he called home. There in the barracoon, as there in his Alabama home, Kossola was transfixed between two worlds, fully belonging to neither.

This quote is what sparked my interest in a spatial investigation of Hurston’s Barracoon and Kossola, the subject of Hurston’s interviews in this book. Kossola lived through various environments: his home in Bantè, treacherous slave ships, tiny barracoon that held the enslaved prisoners, and American soils in Alabama. It is the centralized narrative of Kossola’s spatial transfixion between water, land, and home that stretches him among multiple places. In the beginning quote, the reader sees how space is enveloped in place because, for Kossola, space seems overwhelming here as he is caught between realms, yet not belonging to “no land” or no place due to the violence of his forced journey through multiple spaces and places.

In 2018, Deborah Plant edited Zora Neale Hurston’s book Barracoon, although Hurston began this work in 1927. She meets 86 year old Kossola in Mobile, Alabama. He spent the first 19 years of his life in freedom, and then was sold as chattel and transported on the last American slave ship The Clotida. Surviving the middle passage, he spends 5 and a half years in captivity before gaining freedom from slavery. He and other shipmates built a community called Africatown in Plateau, Alabama. Again, Kossola’s relationship to multiple places and space is unique to his narrative.

In 2018, Deborah Plant edited Zora Neale Hurston’s book Barracoon, although Hurston began this work in 1927. She meets 86 year old Kossola in Mobile, Alabama. He spent the first 19 years of his life in freedom, and then was sold as chattel and transported on the last American slave ship The Clotida. Surviving the middle passage, he spends 5 and a half years in captivity before gaining freedom from slavery. He and other shipmates built a community called Africatown in Plateau, Alabama. Again, Kossola’s relationship to multiple places and space is unique to his narrative.

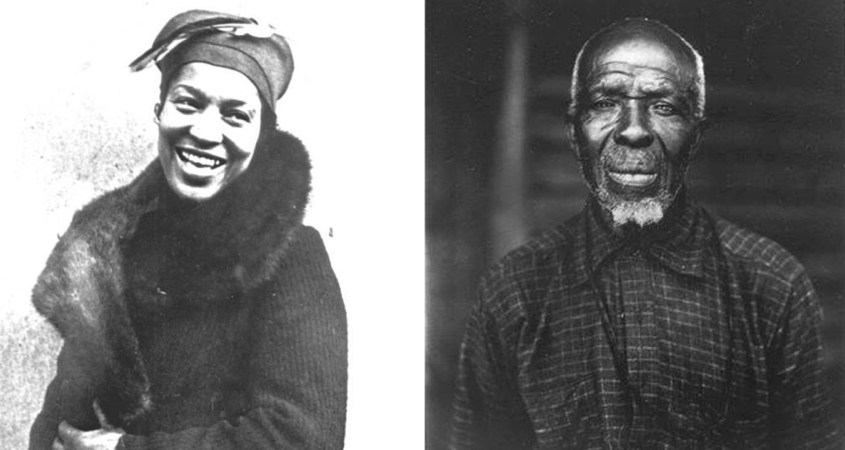

I want to introduce the relationship of space, place, and storytelling that Hurston and Kossola engage in. In later posts, I will review some theories of cultural spatiality to understand environmental awareness while navigating various spaces in this piece. Hurston describes Kossola as a “poetical old gentleman… who could tell a good story.” And in the tradition of the griot in his West African homeland, Kossola tells a story of epic proportion. It is in the telling of the narrative of his own pain and remembered trauma that he carves out a sense of self, although fragmented by the spaces of the past. Yet, Kossola manages to live, despite his ever-changing environments, and through a sense of placelessness in American soil.

The way that this work records Kossoula’s movement through time and space is unique. Plant notices that the book is “a kind of slave narrative in reverse, journeying backward to barracoons, betrayal, and barbarity. And then even further back, to a period of tranquility, a time of freedom, and a sense of belonging.” In this sense, Kassoula goes through real time and space in order to recount his transitions through multiple disruptions, seeing his humanity objectified through various enslaving, capitalist transactions….it would seem that his environmental awareness is expanded through this multilayered experiences throughout multiple lands.

Kossola constantly dreams of “Affica soil” throughout Hurston’s recordings. He always continues to reference the materiality of the soil throughout his story, as a place longed for but could never be obtained. When Hurston first calls him by his real name (Kossola instead of his American name “Kudjo“), Kossola exclaims,

Kossola constantly dreams of “Affica soil” throughout Hurston’s recordings. He always continues to reference the materiality of the soil throughout his story, as a place longed for but could never be obtained. When Hurston first calls him by his real name (Kossola instead of his American name “Kudjo“), Kossola exclaims,

“Oh Lor’, I know it you call my name. Nobody don’t callee me my name from cross de water but you. You always callee me Kossula, jus’ lak I in de Affica soil!”

In this quote, Kossola maps out a place that historically and constantly excludes his real name (“Nobody don’t call me my name from cross de water”), and he connects the knowledge of his name to a material substance and a place simultaneously (“You always callee me Kossula, jus’ lak I in de Affica soil!”). His real name invokes a spatial identity that seems to be oppressed by American soil. Throughout this book, we can see how place impresses upon Kossola’s actions and identity, as he travels through multiple captive and “free” spaces.

——

Cover Image: Image of a “barracoon”

Image 1: Cover of Barracoon

Image 2: Picture of Zora Neale Hurston (Left) and Kossola (Right)