Sunday March 4, 2018

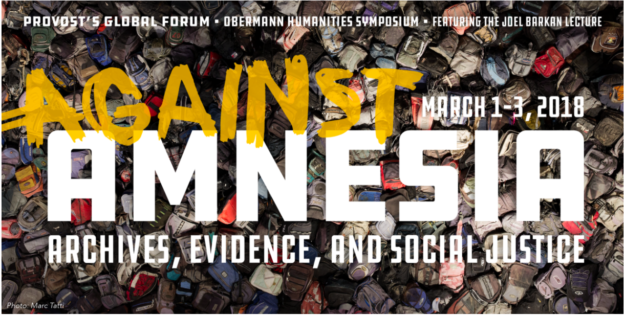

Curators, archivists, academics, artists, and activists from Canada, the U.S., and South Africa spent three days talking together about how we make meaning from and with archives at Archives Against Amnesia , a University of Iowa Global Provost’s Forum and Obermann Center for Advanced Studies Humanities Symposium.

It was a really thoughtful event, carefully crafted and full of considerate details. It was also a space where dissensus was productive and in which people spoke openly about the institutional and structural challenges many of us have confronted when doing social justice oriented archival and cultural heritage work.

I was struck, as we wrapped up yesterday, by several strong threads that wove throughout the three days – for now I’m going to focus on just the performance thread, but I’ll return to the others in follow up posts.

International engagement and human rights were perhaps obvious topics for the former US National Archivist and human rights archives expert, Trudy Huskamp Peterson. Huskamp Peterson asked the audience to participate by reading individual articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which then set up her discussion of a relevant example for each from across the globe. This accomplished two things in rather elegant and economical fashion: it engaged us in speaking the words of the UDHR, a process that was performative, embodied, and temporal in ways that are meaningfully different from those of reading silently or being read to. Even as many of us commented upon the scary resonances in each article for this historical moment here in the United States, Huskamp Peterson’s global examples forced us to think about the power of archives, records, and documentation in a much larger framework.

Huskamp Peterson did a really marvelous job of not simply celebrating the possibilities of archives to attest to human rights violations, but also pointing instances wherein modern records/documents are being used in the service of violating some of those human rights. I was asked to read article one, which reads:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

She then shared the story of

Aiden and Ethan Dvash-Banks, two boys born to a gay couple who have been denied equal citizenship rights in the United States through DNA testing

As Huskamp Peterson noted, while they may have been born together, they are not currently born “equal in digital and rights.”

The performative element created by Huskamp Peterson’s invitation for us to read for her carried through Ojibwe filmmaker Adam Khalil’s presentation, which wove together the film The Violence of A Culture Without Secrets and live cultural theorizing, pushing us think hard about colonial settler paradigms in western archives and museums. You can read about the work here and read more on the Khalil brothers’ other work here.

Among my favorite moments in this discussion was Adam’s observation that the tools of anthropology and ethnography could/should be turned on the oppressor. In order to understand, in Khalil’s example, why white people have long enjoyed dressing up and playing Indian.

Sheri Parks’ “Direct Descendant in the Archives—A Scholarly and Emotional African American Family History” powerfully wove together scholarly archival work and personal narrative, performed in real time as Parks read from her forthcoming non-fiction/autobiographical book. Facing head-on the challenges and benefits of doing personal work as an academic, Park was honest about the audiences for whom she writes in this work and the consequences of that in an academic system that privileges “20 pages of footnotes.” If you’re an administrator wanting to advance “publicly engaged work” at your institution – you might consider asking Parks to talk about what the “kiss of death” was for her in terms of using this work in university performance and promotion reviews.

Parks also modeled for us an unflinching willingness to confront family, regional, and international racial formations in doing a personal history. Thereby bringing to life, rather literally in so far as this is her life, the consequences of enslavement, emancipation, passing, and intergenerational differences in engaging white supremacy and black life in the United States.

Two very different but equally wonderful films by Jazz musician John Rapson and playwright Lisa Schlesinger, followed Parks’ non-fiction embodied storytelling. Rapson’s film included music and spoken work that held up a mirror to white supremacist and settler language in the context of the American western genres, deploying mixed linguistic and generic modes. Rapson’s story is based on the true story about a young Afghan who left home near the Khyber Pass, wandered through India, and ended up eventually in Sheridan, Wyoming, selling tamales. From the initial story published in The New Yorker, Rapson created a thirteen-movement work about immigration, citizenship, and home. His music includes lilting Western ballads, gentle Mexican waltzes, folk melodies from the East, evocative tone poems, and raucous ragtime that complement period photographs. Schlesinger screened her short documentary film, Three Boats: Iphigenia at Lesvos which is part of the multi-modal and multi-event Iphigenia Project (which will include a documentary opera – more info, including the script for the play here). Honestly, I cried. It’s gorgeous even at this early stage of their work and I was deeply moved by the discussion that followed, including the sensitivity to the changing political and ethical realities for Syrian refugees.

While performance as such was not the focus of Saturday morning’s session by Sarah Dupont and Gerry Lawson (“Whose Nation? Whose Archives? Indigenaeity in Canada”), their presentation was a really generous performance of engagement with place and people, as well as modeling some really great tools for educating non-indigenous audiences in the processes and protocols of indigenous scholarship and engagement. They were also deeply personal in a way that mirrored Parks’ presentation the night before.

Beyond their own style, because they were talking about Indigitization Project, both linguistic and cultural performance of memory, song, ritual, and more were integral to Sarah and Gerry’s discussion of indigenous archival practice. I could write a short essay on Sarah’s amazing discussion of her “grant advocacy” and how it performs care for the communities she’s engaging in British Columbia, but that will wait for another time (and perhaps Sarah’s own writing on the topic, if we’re lucky. I’ve asked both Sarah and Gerry to write about their work for HASTAC).

For the final session, organizer and Obermann Center Director Teresa Mangum asked Rachel Williams and I to share a bit of our work and to talk about how we decide when/if to use art – graphic novels in Williams’ case and interactive mixed media performance in my case – to engage with archival materials. Williams shared with us the gorgeous pages of her forthcoming graphic novel on the 1943 Detroit race riots and spoke about the power of images to focus attention on the stories of those who do harm, in addition to recovering the too often forgotten stories of those harmed.

I spoke about the work I’ve been doing with Nikki Stevens using haptics and sonification to share sensitive data sets, particularly from the Eugenic Rubicon project (this is a collaboration with Alexandra Minna Stern and her team at the University of Michigan and an outgrowth of work I’ve done with Jessica Rajko at ASU). In response to “why art” – here is my answer:

The records of eugenic sterilization in California include the personal medical and mental health information of 20,000 people who were recommended for sterilization in the 20th century. While some of this data is aging out of HIPAA protection, I still prefer to use the highly abstracted media of numbers transformed into touch and sound as a way of honoring those who are represented in the records. I do not want to be re-traumatizing communities. I do not assume that I can decide for others whether or not it has been long enough. At the same time, I feel strongly that we cannot let the reality of human rights violations remain hidden and want to be able to communicate the affective power of this archival record by returning numbers taken from bodies violated to bodies that are willing to witness. So I make what others call art (I’m more comfortable with multimedia experience) that I consider creative critique – both artistic and scholarly. For me this is performative work and I was pleased to see so many others thinking about performance in/with archives this weekend.